Choreographing Connection

Choreographing Connection is Lynn Panting’s professional practice blog, offering reflections on her artistic work and the arts sector at large. Through her lens as a director, choreographer, and intimacy professional, she shares think pieces, resources, strategies, and insights that speak to the evolving landscape of the performing arts.

Director’s Diary: Loves Labour’s Lost — Building the World with a Soundtrack

A good playlist becomes a unifying thread that ties the world together before we’ve even entered the room.

For me, music is a shortcut to world building. It can capture tone, texture, and emotional stakes in ways that words alone often can’t. It helps me tap into atmosphere, relationships, and vibe. It’s also one of the fastest ways to start building a shared language with my collaborators.

A good playlist becomes a unifying thread that ties the world together before we’ve even entered the room.

Sometimes I’ll play a track to open rehearsal and drop us into the atmosphere. Sometimes we’ll use the music to find rhythm or gesture or help develop a movement vocabulary. It’s not about dancing to the music—it’s about letting the sound shape how we move through the world of the play.

The Sound of Love’s Labour’s Lost

For Love’s Labour’s Lost, two songs arrived almost instantly, like bookends:

“Poets” – The Tragically Hip

“Rivers and Roads” – The Head and the Heart

“Poets” is instantly recognizable—nostalgic, energetic, cheeky. It’s raw and clever, buzzing with bravado. It perfectly locates us and sets the tone for Team Navarre.

“Rivers and Roads” is the alternative to Shakespeare’s “banger” “The Owl and the Cuckoo” which ends the play. It’s a song about distance—about the ache of growing apart even when you mean to stay together. It’s at once melancholy and anthemic and has big sing along energy.

Other songs include:

“Take Me Out” – Franz Ferdinand, a classic party tune with swagger.

Jackie and Wilson” – Hozier, a sweet declaration of love with an R&B feel.

Mystical Magical” – Benson Boone, all candy floss, optimism, and falling in love.

The playlist isn’t static. It evolves with the show. Sometimes a song I added on a whim becomes essential. Other times, a track falls away once we’re in the room. That’s part of the magic. The music shifts as we discover more about the world we’re building.

Check out our full Spotify playlist to hear more of the music behind the world of Love’s Labour’s Lost:

Love’s Labour’s Lost – Playlist on Spotify

Next up: digging into the academic world of Navarre and why Memorial University’s campus is the perfect setting for this play.

The Perils of Being “Good to Get Along With”

Let’s start building, activating, and actioning cultures where we are actively good to one another, and not passively “good to get along with”.

A couple of years ago, I was injured at work.

Really injured.

Injured in a way that I can’t go back from, only forward.

I’ve always been invested in advocacy: pushing for safer, more inclusive, more thoughtful spaces in the arts. But that injury cracked something wide open. It changed how I move through the world and how I show up in creative spaces.

With that as context, I want to talk about the perils of being “good to get along with.”

The Problem with Being “Good”

Let’s start with the obvious: we’re in an industry that thrives on personal relationships. Opportunities come through trust and collaboration. We’re told that being “easy to work with” is an asset, something that will keep us booked and blessed.

But there’s another layer to this. A gendered one. A cultural one.

As a woman, I’ve been conditioned to do the labour of getting along. Of keeping the vibe light. Of not being “difficult.” I have lived in fear of the perception that someone might think I’m a bitch.

Lately, I’ve been asking myself: Why have I worried so much?

I have been “good,” “easy,” “silent”… and as such, complicit.

And you know what?

—It hasn’t made my work better.

—It hasn’t made my life easier.

Meanwhile, others are not “good to get along with” at all.

Some are rude, erratic, dismissive, even violent. And yet, they continue to move through this industry with impunity.

Their power protects them. My “good” behaviour supports their tyranny and keeps me (and others) small.

So What Now?

Instead of striving to be “good to get along with”, I want to offer some alternatives.

Be professional.

Meet your commitments. Communicate clearly.

Be boundaried.

Know what is and isn’t yours to hold.

Be generative.

Bring your ideas, your insight, your artistry. Show up with an offer.

Be accountable.

To your craft, your collaborators, and yourself.

Be Good to One Another

Let’s be good to one another.

Not palatable. Not polite. Not easy.

But honest. Caring. Courageous.

Being good to one another is active. It means asking hard questions, respecting boundaries, and showing up with integrity. It means naming harm, taking responsibility, and holding space for growth.

Let’s start building, activating, and actioning cultures where we are actively good to one another, and not passively “good to get along with”.

It’s You. You’re the Problem. It’s You: A Reflection on Power, Perception, and Accountability in the Arts

It’s a lot easier to spot harm when you’re on the receiving end of it. But what happens when the power begins to shift? When you're no longer the scrappy underdog, but the person others listen to?

I’ve been sitting with this one for a long time.

What I’m about to say comes from years of observation, experience, and reflection, I want to begin by acknowledging that the subject matter is nuanced and deeply intersectional.

The broader conversation about harm, power, and responsibility in the arts is far more complex than what I’ve laid out here. This post isn’t meant to be the whole story, it’s just a thread I feel ready to pull on.

I also want to acknowledge my own position: I am a white woman with strong family ties to the local arts community. That comes with privilege—access, safety, and visibility that many others have not been afforded. I do not speak from a place of neutrality, and I am certainly not exempt from the dynamics I’m about to explore.

Post #MeToo, post-George Floyd, post-the-public-reckoning-with-the-genocide-of-Indigenous children in residential schools, post-COVID, what has emerged is a growing, uneasy honesty in the arts.

In 2022, Jesse Green wrote a piece for The New York Times titled “Is It Finally the Twilight for Theatre’s Sacred Monsters?” The subtitle cuts to the bone: “Many of the great men who helped America create its classics and institutions and acting style were tyrants. We need to cut them loose.” It’s a solid article. What struck me more than the article itself was who was sharing it.

It was artists, directors, and administrators—many of whom, in my experience, are not unlike the so-called "sacred monsters" the piece condemns.

How do you know when you are the problem?

So here’s the uncomfortable question I want us to ask: How do you know when you are the problem?

It’s a lot easier to spot harm when you’re on the receiving end of it. But what happens when the power begins to shift? When you're no longer the scrappy underdog, but the person others listen to?

If you’ve been working in the arts for some years, if you’re regularly getting hired, and being paid for your work, you are no longer emerging. You are visible. You are powerful. And you hold influence (of varying degrees- again, intersectionally is reality), whether you recognize it or not.

That’s where the danger lies.

Most of us don’t feel powerful because we still carry the wounds of rejection and struggle. But being wounded doesn't make you harmless.

How do you stay in check?

Open Communication: Build cultures where people can speak up safely. Really speak up. Not just offer critiques you’re comfortable with.

Truth to Power Mechanisms: Don’t just say you're open to feedback. Create actual systems for it. Include a third party that does not have a conflict of interest.

Diversify Your Circle: If everyone around you agrees with you, you're probably in an echo chamber. Surround yourself with people who challenge you kindly, constructively, and regularly.

Self-Interrogation: Make it part of your practice to ask hard questions of yourself. Why do I make the choices I do? Who benefits? Who is being left out?

Do Your Words and Actions Match? It’s easy to talk about transparency, collaboration, or inclusion, but are you doing those things when it matters? In my experience, many folks genuinely intend to act differently but simply haven’t practiced it. Good intentions are nothing without follow-through.

Be Willing to Change: The industry is shifting. If your practice hasn’t changed in the last five years, you may be clinging to a version of yourself, or the world, that no longer exists.

None of this is easy. It’s uncomfortable, sometimes painful. But choosing not to engage with this work doesn’t make the discomfort go away. It just pushes it onto someone else. That person, that “someone else,” is likely less powerful than you.

If you’re not actively working to dismantle harm in your spaces, you are reinforcing it, however unintentionally.

Building the Movement Design for There’s Nothing You Can Do

One of the central questions we faced was: how can the actors “dance themselves to death” without actually harming themselves in the process?

There’s Nothing You Can Do, RCA Theatre Company, 2025

Movement Direction, Choreography, Intimacy Direction by Lynn Panting

photo by Marie Dionne Photography

Working on this piece was a rare and rich experience.

I first encountered the play, by the fabulous Cole Hayley, during its debut at the National Theatre School of Canada and was later invited to participate in a movement dramaturgy workshop during its second development phase. That early involvement allowed me to explore the practicalities of the work before committing to any formal movement design.

One of the central questions we faced was: how can the actors “dance themselves to death” without actually harming themselves in the process?

Before rehearsals officially began, we held a four-day movement workshop with the full cast. This time was essential. It allowed us to establish a shared vocabulary, experiment with tools and tactics, and build the kind of ensemble trust that supports deep physical storytelling and builds stamina. The goal wasn’t to set choreography—it was to create a process that felt authentic, responsive, and sustainable.

The Design Toolbox

The movement design I landed on is not a single style or aesthetic. It’s a collection of tools the actors can draw on, adjust, and reinterpret to suit their character’s arc and moment-to-moment needs.

Core Principles of Variation: Scale (big/small), tempo (fast/slow), level (high/low), and pathway (curved/straight) help shift energy and tone without words.

Laban Technique: Using oppositional pairs (like bound/free flow, heavy/light weight, direct/indirect movement) provides a physical lens for emotional choices.

Intensity Scale (0–10): Allows actors to safely gauge and modulate how much they’re putting into each moment.

Locomotor Vocabulary: Shared movements like crawling, rolling, spiraling, and jumping help break habitual patterns and create physical contrast.

Kinetic Layering of Symptoms: I used the technical language that described the physical symptoms of illness, trauma, substance use and withdrawal as an additional layer. Rather than labelling internal states with emotional language (e.g., “anxiety” or “fear”), actors are encouraged to use the technical, observable language of the body—such as pacing, fidgeting, trembling, shallow breathing, or sudden stillness.

This technique, focusing on what the body does, rather than what the mind feels and thinks, removed unnecessary emotional weight.

Shared Dance Vocabulary: A collection of physical motifs we all know—but that each performer expresses differently. The result is cohesion without sameness.

photo by Marie Dionne Photography

Miriam

Miriam is a unique character—the only one whose full movement journey we witness from beginning to end, and then back again. I was incredibly fortunate to work with actor Nora Barker, whose work and precision brought the role to life in unexpected and layered ways.

Miriam’s physical journey begins as a slight vibration. The script specifies that these gestures gradually grow into recognizable dance moves—flossing, jazz hands—allowing us to lean into the humour of the moment while maintaining its eerie undercurrent. As the movement builds and Miriam speaks less, her body begins to do the talking. She interacts with the set and the other characters in ways that reflect, comment on, and sometimes even mimic the world around her.

Her body becomes both mirror and critic, revealing an internal landscape that words can’t access.

Eventually, Miriam foreshadows the tragedy that looms over Act One. Her resulting solo is a complex blend of resistance and surrender, ecstasy and pain. It was a challenging balance to strike—one that required both control and abandon—and I was lucky to have Nora as a collaborator throughout that process.

When Miriam returns at the end of Act Two, it was clear to me that her vocabulary had to evolve. We couldn’t repeat what had come before. The character has been altered—something irreversible has happened. Her movement remains constant, but it’s no longer rooted in contemporary language. It now belongs to something more ancient.

We drew from the iconography of ancient statues and Greek mythology to develop a new vocabulary: poses, cycles, and gestures that speak to myth, legacy, and ritual. This movement is still kinetic, still present, but it exists on a deeper frequency—something more ancestral, almost divine. It becomes a kind of embodied mythmaking that starkly contrasts the rest of the ensemble, who haven’t been infected with dance fever for as long.

photo by Marie Dionne Photography

Act 3: Moving Together While Apart

One of the most exciting and difficult parts of the show is Act 3, when each character becomes visually and emotionally isolated. They stop sharing space, storylines, and in some cases, even time. But the ensemble never stops moving together.

I created a detailed movement score for each line of text that draws attention to the speaker and allows the others to rest.

While one actor speaks the others would take that time to transition to their next movement, thus giving the impression that the body drives the text.

Even when disconnected, the performers remain in tune—building the kind of support structure that allows for deep risk onstage.

Final Thoughts

Dance is magic. At its core, this movement design is about connection—to one another, to the body, to the audience, to the heart of the text.

The Rise of Movement Theatre: What It Means for Rehearsal Rooms

We are in a moment where audiences are increasingly hungry for the visceral, for the felt. Dance and movement theatre meet that moment beautifully, but only when the process honours what this form requires.

Remnants, White Rooster, 2019

Movement Direction: Lynn Panting

Photo by Vaida Vaitkute Nairn

There’s a welcome shift happening in the performing arts: movement is having a moment. From full-length dance theatre works to plays with carefully integrated choreography, physical storytelling is becoming central to how we make meaning onstage.

I’m thrilled to see more dance and movement-based work in rehearsal rooms and on stages. But as this shift happens, I want to offer a few reflections, particularly for those who are new to movement-rich processes or just beginning to integrate physical storytelling into their work.

Dance Takes Time

Movement isn’t filler, it’s form. And it demands time. While a page of text might take an hour to rehearse, a single minute of choreography can take several hours to generate, teach, and refine. Movement needs repetition. It needs to land in the body. And that means your rehearsal calendar needs to reflect that reality from the start.

Shared Vocabulary Matters

You may be working with artists from diverse training backgrounds:someone with a ballet degree, another from a clowning tradition, someone else with a theatre or musical theatre foundation. All are valid. All can enrich your piece. But without a shared vocabulary, you risk misalignment. Ensemble-building becomes essential, not just for connection, but to establish common ground in how the body is used, read, and responded to in the work. It’s not about homogeneity; it’s about coherence.

Creative Leadership Counts

Another essential consideration is leadership. Does your director have a background in dance or a working movement vocabulary? Are they open and collaborative with a movement director or choreographer? Directors don’t need to be movement experts, but they do need to respect and support the process. When leadership is dismissive of the physical score, or simply unaware of what it takes to build it, the work suffers. Good creative leadership creates space for movement to thrive as a core element of storytelling, not as an afterthought.

Adjust Your Expectations

The standard “48-hour week” model doesn’t translate cleanly to movement work. Especially if the cast is new to this process. You’ll need to build in time for proper warm-up, cool-down, hydration, and rest. You may need to adjust how you tech the show to protect performers physically. Movement-based work requires a trauma-informed and stamina-aware approach, one that considers not just time in the room but the toll that time takes on the body.

One Size Does Not Fit All

It’s essential to sit down and assess the needs of your specific production at every stage. There is no universal rubric. Is the piece five minutes or ninety? Is it fully choreographed or loosely scored? What is the cast’s movement experience? What are the physical and emotional demands of the work? Are shoes, costumes, or set pieces going to affect how the piece moves and will they be needed earlier than in traditional theatre processes? Can you build in rest breaks during rehearsal and during the show itself? What backstage supports are needed to make the process safe and successful? What first aid resources are necessary? These questions deserve attention, not as afterthoughts but as part of the production plan from day one.

We are in a moment where audiences are increasingly hungry for the visceral, for the felt. Dance and movement theatre meet that moment beautifully, but only when the process honours what this form requires.

Let’s be ready for it.

Hamlet Doesn’t Need to Be Sad — Hamlet Needs to Look Sad: Supporting Sustainable Practices in the Performing Arts

There’s a misconception in the performing arts that to create powerful, moving work, you have to suffer for it. That emotional exhaustion is part of the job. That giving your all means giving everything. But that’s not artistry… that’s burnout. And it’s not sustainable.

There’s a misconception in the performing arts that to create powerful, moving work, you have to suffer for it. That emotional exhaustion is part of the job. That giving your all means giving everything. But that’s not artistry, that’s burnout. And it’s not sustainable.

One of my favourite refrains when teaching, directing, or building movement is: “Hamlet doesn’t need to be sad, Hamlet needs to look sad.” It’s a simple line, but it carries an essential truth: performers are not the roles they play. You don’t have to drag yourself through the emotional trenches to deliver compelling work. What you need are the tools to portray complexity safely and effectively.

Sustainability in performance is about longevity, artistry, and care. It’s not about proving how hard you can work, it’s about building containers that let you keep working.

Here are a few of the strategies I return to again and again:

Set Expectations Early

Whether it’s a traditional script or a devised movement piece, we have to ensure that the time and resources match the task. A movement-heavy piece? It likely needs workshops ahead of rehearsals or extended prep time. An emotionally demanding script? You’ll need boundaries, closure practices, and time to reset. Matching scope to schedule isn’t a luxury, it’s a responsibility.

Structure Rehearsals for Human Bodies

An eight-hour rehearsal day might work on paper, but not in a body. Particularly in dance and movement-based processes, shorter, focused rehearsals, with time for warm-up, cool-down, and rest, are far more effective than pushing to the brink. Respecting the physical and emotional limits of your cast isn’t coddling. It’s craft.

Use Language That Supports Safety

Instead of asking an actor to “act sick,” I’ll describe what that looks like physically: indirect pathways, laboured breath, slower tempo. Instead of labelling a character as “anxious,” I might offer movement qualities like percussiveness, darting eye focus, or bound energy. This creates distance between character and performer, a healthy, helpful distinction, and gives performers something doable, not something felt.

Develop Skill, Not Sacrifice

Creating work that is compelling, precise, and alive doesn’t mean accessing personal trauma. It means learning how to use your body, your breath, your voice, and your imagination with clarity and care. Technique isn’t just for class, it’s what keeps us safe when the stakes are high.

I care deeply about building a performing arts culture where we are both excellent and well. Where rehearsal rooms are places of rigour, joy, and humanity. Where a fulfilling life outside of rehearsal is seen as essential, not optional. Because when we take care of the artist, the art gets better.

Hamlet doesn’t need to be sad. Hamlet needs to look sad. Let’s build processes that let us do the work without losing ourselves in it.

Tools for Expressing Discomfort in Rehearsal or Performance

In any rehearsal or performance involving intimacy, physicality, or emotional vulnerability, it’s important to have clear and accessible ways to express discomfort.

Consent is a Practice and is Always Revocable

In any rehearsal or performance involving intimacy, physicality, or emotional vulnerability, it’s important to have clear and accessible ways to express discomfort. The following outlines several verbal, non-verbal, and post-scene tools that you can use to communicate your boundaries at any time. These options can be used alone or in combination, and you are always encouraged to propose your own.

Verbal Tools

These phrases are designed to pause or adjust the action in a neutral, respectful way.

“Can we pause?”

“Hold.”

“I need a break.”

“I’m at capacity.”

“That’s a no for me.”

“I need to step out.”

Verbal Stoplight System

The meaning of each colour must be discussed and agreed on in advance.

Green – All good

Yellow – Proceed with caution / I’m unsure

Red – Stop immediately

Non-Verbal Tools

These are helpful when speaking isn’t possible or if you're in the middle of a scene.

Hand Raise

“Time Out” Signal

Hand to Floor

Silent Step Back

Stop and Drop

Post-Rehearsal Tools

Boundaries can shift. You don’t have to speak up in the moment to be heard.

Private Check-Ins – One-on-one conversations before or after rehearsal.

Written Communication – Text or email if verbal communication feels too difficult.

Scheduled Debriefs – Built-in time to reflect with the intimacy professional or director.

You Are Not Alone

Your safety, autonomy, and comfort are essential. You never need to explain or apologize for expressing a boundary. Consent is always revocable.

You can change your “yes” to a “no” at any time.

Let’s build rehearsal rooms that are creative, collaborative, and rooted in mutual care.

Creating Connection: The Special Handshake for Intimacy Scene Partners

By creating a unique ritual, intimacy scene partners can foster a deeper bond, navigate the emotional demands of their work with greater ease, and bring authenticity to the relationships they portray on stage.

Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare by the Sea, 2023

Intimacy Direction and Choreography: Lynn Panting

When it comes to intimacy direction, fostering trust and connection between scene partners is essential. These relationships often require a level of vulnerability and collaboration that goes beyond standard rehearsals. While tapping in and tapping out are excellent boundary-setting practices, introducing a personalized ritual, like a special handshake, can add an extra layer of connection, support, and intention.

A special handshake is a small, private ritual shared exclusively between intimacy scene partners. Done before and after intimacy rehearsals and at the top and tail of performances, this gesture acts as a grounding mechanism, a signal of mutual respect, and a boundary between self and character.

Why Create a Special Handshake?

Builds Trust and Connection

A unique handshake is a shared moment that belongs solely to the scene partners. It fosters a sense of camaraderie and mutual care, reinforcing the trust necessary to explore vulnerable material.

Creates a Sense of Safety

The ritual serves as a physical reminder that both partners are entering a safe, consensual space. It anchors performers in the present moment and provides a tangible way to signal readiness and mutual support.

Sets Intention

Performing the handshake before a scene or rehearsal allows partners to set a shared intention for their work, whether it’s focusing on honesty, collaboration, or mutual care. Ending with the handshake helps partners transition out of the scene, returning to their personal selves.

Reinforces Closure

After an intimate scene or performance, the handshake provides a sense of closure, helping performers separate their character work from their own emotions and experiences.

How to Create a Special Handshake

Collaborate on the Gesture

The handshake should be co-created by both partners to ensure it feels meaningful and authentic. Discuss what elements you’d like to include — it can be as simple as a series of taps or as elaborate as a choreographed sequence.

Make It Unique

The handshake doesn’t have to look like a traditional handshake. It could involve fist bumps, finger snaps, a high five, or any other gestures that feel right to the partners. The key is that it’s unique.

Keep It Intentional

Even if the handshake is playful, it should be performed with intention. This isn’t just a fun ritual; it’s a tool for connection and grounding.

Practice Together

Before integrating the handshake into rehearsals and performances, practice it a few times together. This helps solidify the movement and ensures it becomes second nature.

Use It Consistently

The handshake should bookend every intimacy rehearsal and performance. Its consistency reinforces its purpose and helps create a reliable routine.

When to Use the Special Handshake

Before Intimacy Rehearsals

Perform the handshake to signal that both partners are ready to enter the rehearsal space and engage in the work.

After Intimacy Rehearsals

Use the handshake as a way to close the session, ensuring both partners feel supported as they transition out of the work.

Before Performances

The handshake becomes a grounding ritual before stepping on stage, reinforcing trust and connection in the moments leading up to the performance.

After Performances

End the show run with the handshake to acknowledge the shared effort and return to your personal selves.

Benefits for Performers and Productions

Strengthened Bonds: The handshake deepens the connection between partners, making their onstage chemistry more authentic.

Emotional Resilience: Rituals like this help performers process and separate their character work from their personal lives.

Professionalism: A special handshake demonstrates the care and intentionality that intimacy direction brings to a production.

Audience Impact: When performers feel connected and safe, it shows in their work, resulting in more compelling and authentic storytelling.

A special handshake is more than a gesture, it’s a commitment to trust, care, and collaboration. By creating a unique ritual, intimacy scene partners can foster a deeper bond, navigate the emotional demands of their work with greater ease, and bring authenticity to the relationships they portray on stage.

The Importance of Tapping In and Tapping Out: A Boundary Practice for Rehearsals and Performances

Tapping in and tapping out is more than a ritual, it’s a transformative practice that empowers performers to navigate the emotional and physical demands of their work with clarity and care. By fostering boundaries, consent, and trust, it creates a foundation for artistry that is both bold and sustainable.

The rehearsal room and performance stage are places of vulnerability, exploration, and transformation. For performers, stepping into a character or an emotionally charged scene often requires opening themselves up in profound ways. This intensity makes it essential to establish practices that help protect their emotional and mental well-being. One of the most effective boundary-setting tools in creative spaces is the practice of "tapping in and tapping out."

This simple yet powerful ritual provides performers with a clear framework for entering and exiting the emotional and physical demands of rehearsal and performance.

What Does Tapping In and Tapping Out Mean?

Tapping In: A performer actively signals they are ready to step into a scene, exercise, or performance. This might involve a verbal acknowledgment, a gesture, a unison clap, a special handshake, or simply saying “I’m in.”

Tapping Out: A performer signals that they are stepping away, marking the end of their participation for that moment. This a bookend ritual action similar to their chosen “tap in”.

This practice ensures that everyone in the room is aware of when a performer is engaging with or stepping away from the work, fostering clarity, consent, and mutual respect.

Why Tapping In and Tapping Out Is Important

Sets Clear Boundaries

Performers often pour themselves into their work, blurring the lines between character and self. Tapping in and out provides a structured way to delineate where the performance begins and ends, protecting the performer’s sense of self.

Fosters Consent

The practice creates a culture of consent by giving performers agency over when and how they participate. It emphasizes that engagement with the material is a choice, not an obligation, ensuring performers feel safe and respected.

Encourages Emotional Regulation

Emotionally intense scenes can linger, affecting performers even after they leave the stage. Tapping out serves as a conscious ritual to help performers disengage from the emotional demands of the work, reducing the risk of emotional overwhelm or burnout.

Builds Trust and Collaboration

When everyone in the room follows the practice of tapping in and out, it fosters a collective sense of responsibility and respect. It builds trust between performers, directors, and crew, creating an environment where boundaries are honoured.

Enhances Focus and Intention

By requiring performers to actively signal their readiness, tapping in and out encourages mindfulness. It ensures that when performers step into a scene, they do so with full focus and intention, enriching the quality of their work.

How to Implement Tapping In and Tapping Out

Introduce the Practice Early

At the start of the rehearsal process, explain the concept of tapping in and out to the cast and crew. Emphasize its importance as a boundary-setting tool and a way to create a safe, supportive environment.

Create a Ritual

Decide on the specific gestures or verbal cues that will signal tapping in and out. This might include:

Saying “I’m in” or “I’m out.”

A physical gesture like placing a hand on the chest or raising a hand.

A symbolic act, such as stepping into or out of a designated space.

Normalize the Practice

Encourage everyone to use the practice consistently, regardless of the intensity of the scene. Whether it’s a lighthearted exercise or a deeply emotional moment, tapping in and out should become a standard part of the creative process.

Respect the Signals

Ensure that all participants respect the tapping in and out process. If someone taps out, their decision should be honoured without question or pressure to re-engage.

Encourage Reflection

After particularly intense scenes or rehearsals, invite performers to reflect on how they’re feeling. This can be done individually or as a group check-in, providing an additional layer of emotional support.

The Broader Impact of Tapping In and Out

The practice of tapping in and tapping out extends beyond rehearsals and performances. It teaches performers valuable skills in setting and communicating boundaries, which can be applied to their personal lives and other professional settings. It also reinforces the importance of self-care, reminding artists to prioritize their well-being even as they pour themselves into their craft.

By creating a rehearsal room culture rooted in respect, consent, and mindfulness, tapping in and tapping out enhances not only the creative process but also the lives of the artists involved.

Tapping in and tapping out is more than a ritual — it’s a transformative practice that empowers performers to navigate the emotional and physical demands of their work with clarity and care. By fostering boundaries, consent, and trust, it creates a foundation for artistry that is both bold and sustainable.

The Let Go Menu: A Toolkit for Artists in Overdrive

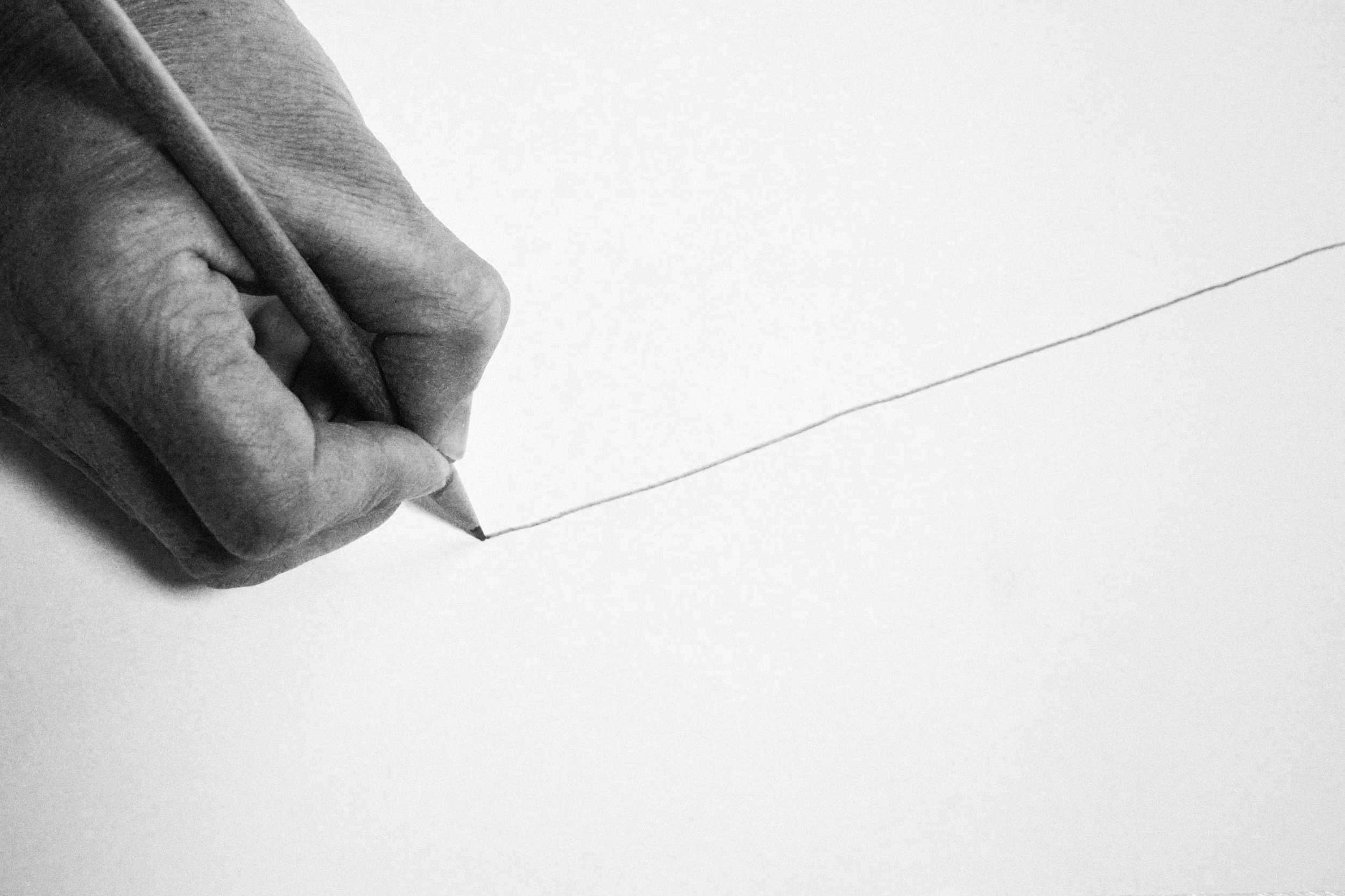

I’ve learned that one of the hardest things for artists to do isn’t creating—it’s letting go.

Letting go of anxiety. Letting go of the fear that we’re not doing enough. Letting go of the pressure to fix, control, or prove something.

I’ve learned that one of the hardest things for artists to do isn’t creating—it’s letting go.

Letting go of anxiety. Letting go of the fear that we’re not doing enough. Letting go of the pressure to fix, control, or prove something.

Whether you're standing in a rehearsal room, sitting at your desk, or lying awake at 3 a.m. overthinking an email, letting go is not a passive act—it’s a practice. It’s something we can choose, and like any physical or artistic practice, we get better with time.

I created a Let Go Menu—a short list of active tools that help me move through anxiety and emotional intensity when it shows up. This menu isn’t about erasing feelings; it’s about responding to them with care.

The Let Go Menu

1. Physical Reset

Sometimes, the body just needs to move to release what the mind is holding.

Shake out your hands and arms

Roll your shoulders and jaw

Do a one-song dance break to shift your energy

Mantra: “This doesn’t live in my body anymore.”

2. Breath Break

Letting go can be as simple as one exhale that says, not mine to carry.

Inhale 4, hold 4, exhale 8

Whisper “I release” on the exhale

Imagine the thought or tension dissolving with the breath

Mantra: “I breathe out the weight. I breathe in space.”

3. Say It & Seal It

Sometimes the act of naming what we’re carrying is enough to set it down.

Say out loud or write:

“I’ve done what I can.”

“This doesn’t need more from me.”

“I’m choosing peace now.”

Then close the book, tab, or room.

Mantra: “It’s okay to stop holding this.”

4. Redirect the Flow

If your brain is stuck, move your focus somewhere that says yes to your capacity.

Walk it off, even for five minutes

Do one small task you can complete

Organize something. Make something. Care for something.

Mantra: “Where do I actually have power right now?”

5. Symbolic Gesture

Create a ritual. Let the body feel the release.

Toss a crumpled note

Light a candle or blow one out

Visualize placing the thought in a box on a shelf

Hold a small stone and transfer the energy into it

Mantra: “I’ve held this long enough. I let it rest now.”

6. Gentle Reassurance

Meet yourself with the same compassion you’d offer a student or castmate.

Place a hand on your heart

Say:

“I am safe.”

“I’m allowed to be okay.”

“I trust myself to return if needed.”

Mantra: “Letting go doesn’t mean I don’t care. It means I care for myself too.”

7. Sing Frozen’s “Let It Go”

Yes, seriously. I do this. Especially when I’m stuck on something ridiculous that I know doesn’t deserve more airtime in my brain.

Belt out the chorus—especially:

Let it go, let it go

Can't hold it back anymore

Let it go, let it go

Turn away and slam the door

I don't care what they're going to say

Let the storm rage on

The cold never bothered me anyway

Laugh at yourself. Lean into the ridiculousness. It works. I feel better every time.

Mantra: “Let it go, let it go” / “The cold never bothered me anyway”

Letting go is not the absence of care—it’s an act of radical self-trust.

So the next time your body says “hold on tighter” and your mind says “spiral faster,” try saying this instead:

“I trust myself to let go. I trust myself to return if needed. I trust myself to know the difference.”

If this resonates, I’d love to know which Let Go Menu item you return to the most.

—L.

Building Trust in the Rehearsal Room Through Movement

A rehearsal space where movement and physical awareness are prioritized is one where trust naturally flourishes. By tuning into our own bodies, connecting with our ensemble, establishing clear boundaries, and embracing movement as a tool for communication, we create a working environment that is both safe and artistically rich.

Trust is the foundation of any successful rehearsal process. When performers feel safe, supported, and connected, they take bigger risks, dive deeper into their work, and create more compelling performances.

While trust is often built through conversation and collaboration, movement and physical awareness play an equally vital role. How we inhabit space, respond to others, and engage with our own bodies all impact the rehearsal room dynamic.

Here’s how directors, choreographers, and performers can use movement to cultivate trust, improve ensemble connection, and create a rehearsal space where everyone can thrive.

Start with Grounding & Physical Awareness

Before performers can connect with each other, they need to connect with themselves. Building trust begins with an awareness of our own bodies—where we hold tension, how we breathe, and how we move through space.

In Practice:

Body Check-In: Start rehearsals with a few moments of stillness or gentle movement, asking performers to notice any areas of tension, fatigue, or ease.

Breath Work: Lead a simple breathing exercise to encourage relaxation and presence. Slow, deep breaths help regulate the nervous system and create a sense of calm.

Non-Verbal Warm-Ups: Encourage exercises that focus on sensation—rolling through the spine, shifting weight, or shaking out the limbs. The goal is to get performers out of their heads and into their bodies.

Use Movement to Build Ensemble Connection

Trust in an ensemble is built through responsiveness—learning to move together, listen with the body, and develop an awareness of others.

In Practice:

Mirroring Exercises: Pair up performers and have one lead a movement sequence while the other follows as closely as possible. This builds focus, non-verbal communication, and trust.

Group Walks and Flocking: Have the entire ensemble walk through the space at the same pace, without speaking. Gradually introduce direction changes, slowdowns, and speed-ups. This encourages group awareness and sensitivity.

Weight Sharing & Contact Work: When appropriate, introduce exercises that involve physical contact, such as leaning into a partner’s back or lightly pressing palms together. This helps performers build physical confidence in each other.

Establish Clear Physical Boundaries

Trust doesn’t mean constant physical contact—quite the opposite. A rehearsal room that prioritizes consent and clear boundaries allows performers to engage fully, knowing their comfort is respected.

In Practice:

Check-In Before Contact: Always establish whether touch is necessary in a scene and check in before initiating it. Simple phrases like “Are you comfortable if I place a hand on your shoulder?” normalize consent-based movement.

Exit Strategy: Encourage performers to speak up or step away if something feels off. Make it clear that their autonomy is valued.

Use Movement to Break Down Barriers

Sometimes, the best way to build trust is to remove the pressure of performance and engage in movement that feels playful and explorative.

In Practice:

Guided Improvisation: Give performers movement prompts (e.g., “move through the space as if you are underwater” or “walk as if you’re being pulled by an invisible string”). This reduces self-consciousness and encourages creative play.

Create a Rehearsal Culture of Listening & Adaptation

Trust isn’t a one-time achievement—it’s an ongoing practice. A movement-aware rehearsal space is one where everyone listens, adapts, and supports each other physically and emotionally.

In Practice:

Active Listening Through Movement: Encourage performers to notice how their scene partners breathe, shift weight, or hold tension—these subtle cues inform connection.

Responsive Rehearsal Blocking: Be open to shifting movement choices based on how performers feel in the moment. Adaptation signals that their instincts are valued.

Regular Physical Check-Ins: Mid-rehearsal, take a pause. Ask, “How does your body feel right now?” Checking in physically helps identify tension or stress before it impacts performance.

A rehearsal space where movement and physical awareness are prioritized is one where trust naturally flourishes. By tuning into our own bodies, connecting with our ensemble, establishing clear boundaries, and embracing movement as a tool for communication, we create a working environment that is both safe and artistically rich.

Intimacy Direction for Non-Romantic Stories

Platonic and familial relationships are central to many narratives, and the physical connections between these characters can be just as complex and powerful.

When you hear the term "intimacy direction," romantic or physically intimate scenes often come to mind. However, intimacy on stage is not limited to love stories. Platonic and familial relationships are central to many narratives, and the physical connections between these characters can be just as complex and powerful.

Defining Intimacy

There are clear industry standards outlining when an intimacy director or coordinator must be employed, and these guidelines are essential for ensuring safety, consent, and professionalism in scenes involving intimacy. However, the benefit of working with an intimacy professional extends far beyond mandated contexts.

Intimacy isn’t solely about romance— it’s about connection. It’s the way people interact and share space. Non-romantic intimacy can be subtle, like a sibling rolling their eyes but leaning on each other for support, or deeply emotional, like a parent embracing a child after a long separation.

By expanding our understanding of intimacy, we open the door to exploring a broader range of relationships with depth and authenticity.

Why Intimacy Direction Matters for Non-Romantic Stories

Fostering Believability

The bonds between platonic and familial characters are often foundational to a story. Intimacy direction helps ensure that these connections feel genuine.

Addressing Physical Boundaries

Even in non-romantic contexts, physical interactions can feel vulnerable for performers. Scenes involving holding hands, comforting embraces, or even a friendly arm around the shoulder require clear communication and consent.

Enhancing Storytelling

The physicality of non-romantic relationships — the way people occupy space together, touch, or avoid touch — can convey volumes about their history and emotional state. Thoughtful movement direction ensures these details enrich the narrative.

Applications of Intimacy Direction in Non-Romantic Contexts

Familial Relationships

Family dynamics are often layered with history, expectations, and unspoken emotions. Movement and intimacy direction can help performers capture these complexities.

Friendships

The intimacy of friendships is unique and multifaceted. Friends often share inside jokes, physical closeness, and moments of vulnerability that require careful direction to feel believable. Intimacy direction can guide performers in creating:

Workplace or Professional Relationships

While less overtly intimate, workplace dynamics often involve proximity and shared emotional stakes. Intimacy direction can be useful for body language and physical positioning to reflect power dynamics.

Communities or Ensembles

Group dynamics in stories often require performers to convey a sense of shared history or unity. Intimacy direction can help to establish connection and demonstrate fractures.

Tips for Exploring Non-Romantic Intimacy on Stage

Prioritize Consent and Communication

Even in non-romantic contexts, performers need clear communication about physical interactions. Regular check-ins and consent-driven practices are essential.

Use Space Intentionally

Proximity or distance can speak volumes about a relationship. Experiment with how characters occupy space together to reflect their dynamic.

Layer the History

Non-romantic relationships often have rich backstories. Work with performers to explore how this history informs their physicality and emotional tone.

Create a Movement Vocabulary

Consider how characters show affection, conflict and indifference. Create repeatable vocabulary for these states that performers can employ.

Non-romantic intimacy is a vital, yet often overlooked, element of storytelling. By giving it the same care and attention as romantic connections, we honour the richness and complexity of the relationships that shape our lives.

Director’s Diary: Love’s Labour’s Lost

This is just the beginning of my directorial journey with Love’s Labour’s Lost. Over the coming months, I’ll be sharing my process, from research and rehearsals to the final performances. I’m excited to document the discoveries, challenges, and triumphs along the way.

A Lifelong Relationship with Shakespeare by the Sea

My journey with Shakespeare by the Sea began as an audience member, watching Shakespeare’s The Tempest come to life in Logy Bay.

As I grew, so did my connection to the company. I transitioned from spectator to assistant stage manager, performer and choreographer: working on productions that deepened my understanding of classical theatre and community building. The company has always been a place of camaraderie, where artists come together to create something larger than themselves. I am proud to be part of that legacy and to step into a new role under the excellent leadership of artistic director of Sharon King Campbell.

Returning to Love’s Labour’s Lost

This year, I have the privilege of directing Love’s Labour’s Lost, a play that holds a special place in my heart. In 2010, I performed in Shakespeare by the Sea’s production of the show, an experience that solidified lasting friendships and key professional relationships. That production was full of joy, scripted (and unscripted) sailors, and unfortunate rain storms, the kind of show that reminds you why you do outdoor theatre in the first place.

Maria, Rosaline, Katherine, The Princess, Loves Labour’s Lost, 2010, SBTS

This is just the beginning of my directorial journey with Love’s Labour’s Lost. Over the coming months, I’ll be sharing my process, from research and rehearsals to the final performances. I’m excited to document the discoveries, challenges, and triumphs along the way.

Stay tuned for more behind-the-scenes insights as we bring Love’s Labour’s Lost to life!

Check out Shakespeare By The Sea for job opportunities, auditions, and show information.

Why I Hate Hate Theatre Warm-Up Games

If you adore a good game of Zip Zap Zop or thrive on the chaos of Big Booty, I see you. I respect you. I even admire your unhinged enthusiasm. But, with love, the anxiety, it’s not for me.

Here it is: I hate theatre warm-up games. I hate them with a deep and fiery passion.

Now, before anyone clutches their pearls, let me explain. If you adore a good game of Zip Zap Zop or thrive on the chaos of Big Booty, I see you. I respect you. I even admire your unhinged enthusiasm. But, with love, it’s not for me. It’s probably not for a lot of people.

The Struggle Is Real (and Neurological)

For those who don’t know, I have a language processing disorder. Warm-up games often rely on quick thinking, split-second decisions, and a touch of chaos, all things my brain finds... horrifying.

I use myself as an example here, but it is clear to me through years of experience that I am not the only one who feels a sense of panic when a director calls for us to circle up for the warm-up game.

The Tailored Warm-Up Advantage

For me, a good warm-up is about getting everyone together, focused and on the same page. As such, I prefer warm-ups that serve and reflect the project we’re working on.

If we’re working on a physically demanding piece, let’s stretch, explore levels, and build stamina.

If it’s a deeply emotional project, let’s start with grounding exercises or simple breathwork.

If connection is key, we can play with shared movement or eye contact that builds trust and serves the creative process.

A tailored warm-up not only prepares the body but also tunes the ensemble to the specific demands of the work ahead. It creates focus and intention—something no amount of Big Booty has ever accomplished (no offence).

The Problem with Competitive Warm-Ups

One of the biggest pitfalls in traditional warm-up games is competition. Games that pit individuals against each other, whether through speed, reaction time, or elimination, can fracture an ensemble rather than unite it.

Competition shifts the focus from collaboration to personal survival, which runs counter to the spirit of most theatrical work. If actors are entering rehearsal with a sense of failure or frustration because they "lost" a warm-up game, it can create unnecessary tension and anxiety that lingers into the creative process. The goal of a warm-up should be to bring the group together, not to separate the quick from the slow or the confident from the uncertain.

When we remove the competitive element from warm-ups, we allow space for a true ensemble to emerge.

A Game-Changer for Inclusivity

What I love most about tailored warm-ups is their accessibility. They make room for everyone, regardless of their comfort and experience level. Tailored warm-ups meet people where they are and bring them together on common ground.

It’s not about ditching fun—it’s about redefining what fun means in the context of our work. For me, there’s nothing more rewarding than watching a group come alive because they’ve found genuine connection through movement or shared focus.

A Word to the Warm-Up Game Lovers

Warm-ups are important, but they’re not one-size-fits-all. By tailoring warm-ups to the project and the people in the room, we can create an environment that feels supportive, and inclusive.

To those who swear by their Zip Zap Zop, I love that for you. I understand the joy of laughter, the release of silliness, and the camaraderie that these games can create. If your team is all on board, I say go for it!

Just know that the next time someone suggests a game of Big Booty, I’ll be over here, leading a slow, intentional warm-up that connects us to the work. And if you still want to shout “Big Booty, Big Booty, Big Booty, Oh Yeah!” at the top of your lungs, that’s fine too! Bless.

I won’t leave you hanging! Check out some suggestions for tailored warm ups here.

7 Tailored Warm-Ups for Meaningful Rehearsals

These exercises foster connection, creativity, and intention, ensuring that every moment of rehearsal is meaningful and aligned with your production’s unique needs.

Tailored warm-ups offer a unique opportunity to prepare for the specific demands of a production. Here are seven intentional and impactful warm-ups designed to align with the needs of your project and ensemble:

1. Physical Precision Warm-Up

Best for: Dance-heavy or physically precise productions.

Start with stretches and alignment exercises to build awareness and readiness.

Introduce repetitive movements like walking in patterns (straight lines, circles, etc.) to sharpen spatial focus.

Transition into movement phrases that echo the choreographic vocabulary of the production.

2. Emotional Grounding Warm-Up

Best for: Emotionally charged or intimate productions.

Begin with deep breathing to center the ensemble.

Engage in reflective exercises, such as a “memory walk,” where actors recall personal moments connected to the play’s themes.

Explore the sensation of “carrying” the invisible emotional weight of your character and how it affects movement.

3. Connection and Relationship Building

Best for: Ensemble-driven or relationship-heavy productions.

Pair actors for walking, eye contact, or mirroring exercises, focusing on subtle movements and eye contact.

Move to trust-building activities like guiding each other through the space.

Create small and large group sculptures representing the production’s central themes or relationships.

4. Text and Story Integration

Best for: Productions with complex scripts or heightened text.

Warm up the voice with articulation exercises and resonance work.

Practice speaking lines while walking through the space, changing direction, pace, or volume to match punctuation.

Experiment with pairing actors, where one delivers a line while the other responds with movement, exploring non-verbal storytelling.

5. Environment and World-Building

Best for: Productions with immersive or thematic environments.

Ask actors to embody the environment. Concentrate on flow, gesture and architecture.

6. Collaborative Creativity Warm-Up

Best for: Devised or collaborative projects.

Start with a “Each One Teach One” exercise where participants build a sequence of movements or gestures together.

Break into small groups to create 3 point of connection that build specific relationship vocabulary.

7. Character-Specific Exploration

Best for: Character-driven productions or solo performances.

Begin by walking through the space as the character, experimenting with pace, posture, and physical energy.

Introduce the physical relationships between characters.

Explore the relationship between character and space.

Why Tailored Warm-Ups Work

Tailored warm-ups don’t just prepare the body, they immerse the ensemble in the heart of the project from the start. These exercises foster connection, creativity, and intention, ensuring that every moment of rehearsal is meaningful and aligned with your production’s unique needs.

It’s Not Magic, It’s Movement: How Mirror Neurons Connect Audiences to Performance

Our brains are wired to connect with movement in a way that feels almost magical. But the truth is, it’s not magic; it’s movement.

Have you ever felt a rush of excitement watching a dancer leap across the stage or an emotional tug as an actor’s body collapses in grief? These visceral reactions aren’t just a product of compelling performances , they’re deeply rooted in science. Our brains are wired to connect with movement in a way that feels almost… magical.

At the heart of this phenomenon are mirror neurons, specialized cells in the brain that fire not only when we perform an action but also when we observe someone else performing an action. This neural mirroring creates a unique connection between the audience and the performers, making movement a powerful tool for storytelling and emotional resonance.

What Are Mirror Neurons?

Mirror neurons were first discovered in the 1990s by researchers studying primates. They noticed that the same neurons fired in the monkeys’ brains whether they were picking up an object or watching another do it. Subsequent research revealed that humans have similar systems, and these neurons play a significant role in empathy, learning, and social connection.

When we observe someone performing a movement, our mirror neurons activate as if we’re performing the action ourselves. This neurological response allows us to feel connected to what we’re watching, even if we’re sitting in the audience.

Cool right?!

Why Does Movement Feel So Personal?

Movement Evokes Emotion

Mirror neurons enable us to experience the emotions associated with movement. Watching a dancer’s fluid motion can evoke a sense of freedom or serenity, while sharp, staccato movements may create tension or unease. When we see someone else move, we don’t just watch it, we feel it, as if their movements are happening within our own bodies.

Movement Bridges the Gap Between Performer and Audience

The activation of mirror neurons blurs the line between the observer and the observed. When we see someone perform, our brains create an internal simulation of their actions and emotions. This shared experience fosters a sense of unity and connection, making live performances particularly powerful.

The Science of Audience Engagement

Mirror neurons explain why audiences feel so connected to performances that emphasize movement:

Empathy Activation: Watching a performer cry, leap, or stumble triggers an empathetic response, making the audience feel as though they are part of the experience.

Heightened Emotional Impact: The brain’s mirroring process intensifies emotional reactions, whether it’s joy during a celebratory dance or tension in a dramatic fight scene.

Memorability: Movement engages the brain in a multisensory way, making performances more memorable than those relying solely on dialogue or text.

How Performers Can Harness This Connection

Performers can maximize the power of mirror neurons by being intentional with their movements:

Embody Emotion Fully: Audiences connect most strongly when performers’ movements are authentic and emotionally grounded.

Focus on Detail: Small, precise gestures can have as much impact as grand, sweeping motions. Subtlety draws the audience into the performer’s emotional world.

Use Rhythm and Flow: The timing and energy of movement influence how it resonates with the audience.

Employ Nostalgia: Certain gestures are universal and embedded in the collective unconscious. Performers can tap into this shared language as a tool to connect with audiences.

Why It Feels Like Magic

The profound connection we feel to movement in performance is the result of a remarkable neurological system. But because this connection is invisible and unconscious, it feels magical.

If you’re intrigued by the science behind mirror neurons and the power of movement in storytelling, here are some resources to deepen your understanding:

Book Recommendations

"The Body Keeps the Score" by Bessel van der Kolk

"The Moving Body: Teaching Creative Theatre" by Jacques Lecoq

"Why We Dance: A Philosophy of Bodily Becoming" by Kimerer L. LaMothe

Article Recommendations

Building the Ensemble: A New Approach to Connection in Performance

For me, the magic of a production is often found in the relationships onstage, the shared rhythms, the collective breath that turns a group of individuals into a world in itself.

Ensemble building with David Lane, Jack and the World’s End Water, NL Puppet Collective, 2016

Movement Direction and Choreography: Lynn Panting

For me, the magic of a production is often found in the relationships on stage, the shared rhythms, the collective breath that turns a group of individuals into a world in itself.

This year, thanks to support from ArtsNL, I’m taking a deep dive into my ensemble-building practice. My goal? To refine, streamline, and articulate the methods I use to foster connection among performers while identifying the core exercises that work universally across different projects.

Why Ensemble Building Matters

Ensemble work reminds us of the power of collaboration. A strong ensemble isn’t just a group of performers who share a stage, it’s a network of trust and mutual support. When performers feel connected, they take greater creative risks, listen more deeply, and generate work that is more compelling and alive.

As a choreographer and director, I’ve always worked instinctively to cultivate this connection. But this project gives me the chance to analyze what works, refine the process, and create a structured, adaptable approach that I can bring to future productions.

What I’m Exploring

The Foundations of Connection

How do we create an immediate sense of trust among performers? I’m revisiting exercises that develop awareness, eye contact, breath synchronization, and group responsiveness, fundamentals that lay the groundwork for deeper collaboration.

Building Chemistry

Performers need to feel safe and confident enough to be vulnerable with each other. I’m examining how my intimacy direction tools can be adapted beyond romantic pairings, fostering chemistry in platonic, familial, and antagonistic relationships.

Tailoring the Process

Ensemble work looks different in every production. A Shakespearean play, a contemporary dance piece, and an abstract movement-theatre production require unique approaches. I’m exploring how to adapt my exercises to fit the world of the piece— while maintaining a core structure that remains consistent.

The Role of Play and Ritual

Play is a powerful tool for creating bonds and ritual fosters a shared sense of purpose. I’m experimenting with how shared physical practices can unify a cast and bring authenticity to their interactions.

What’s Next?

As I refine my approach, I’ll be working with a graphic designer to create an illustrated guide that captures my ensemble-building exercises. I plan to create two versions: one detailed guide for my personal practice and a condensed, accessible version to share with organizations and collaborators.

My goal is to make ensemble building feel as vital and intentional as any other aspect of a production. Connection isn’t just something that happens—it’s something we can cultivate with care, intention, and practice.

I look forward to sharing more as this project develops. If you’re interested in ensemble work, I’d love to hear from you! What exercises or approaches have you found most effective in building connection within a cast?

Why Consent Culture Benefits Every Rehearsal Room

Integrating consent-based practices doesn’t just prevent harm—it enhances artistry, deepens collaboration, and fosters a healthier, more sustainable creative environment.

Pursuit rehearsal, 2020

The rehearsal room should be a place of exploration, collaboration, and trust. Yet, for too long, the performing arts have relied on outdated models of direction that prioritize hierarchy over dialogue, often leaving performers feeling unheard, unsafe, or uncertain about their boundaries.

Enter consent culture—a framework that prioritizes clear communication, mutual agreement, and respect for personal boundaries. While often discussed in the context of intimacy direction, consent culture is valuable for every aspect of the rehearsal process, from choreography to scene work to backstage dynamics.

Integrating consent-based practices doesn’t just prevent harm—it enhances artistry, deepens collaboration, and fosters a healthier, more sustainable creative environment.

How Consent Culture Strengthens the Creative Process

Consent Encourages More Confident Performers

When performers know their boundaries are respected, they take more risks. Instead of shutting down when they feel uncomfortable, they engage fully, leading to more authentic performances.

It Builds a Rehearsal Room Based on Trust, Not Power

Historically, some directors and choreographers have used authority to demand compliance. Consent culture shifts the focus from power to partnership, ensuring that artists feel like collaborators rather than instruments.

It Fosters Better Communication and Artistic Clarity

Establishing consent culture means normalizing check-ins, clarifying expectations, and making room for dialogue. This prevents misunderstandings, allowing everyone to work more efficiently and creatively.

It Reduces Harm and Prevents Long-Term Injury

From a physical standpoint, forcing bodies into movement without consent leads to injury. From an emotional standpoint, ignoring boundaries can cause burnout and trauma. In both cases, consent culture prioritizes longevity over short-term results.

It Creates a More Inclusive, Accessible Rehearsal Room

Not every performer moves or experiences space the same way. A consent-based space makes room for individual bodies, voices, and lived experiences rather than imposing a rigid, one-size-fits-all approach.

Practical Ways to Build a Consent-Based Rehearsal Room

Consent culture isn’t just about what we don’t do—it’s about actively creating a better process. Here’s how to implement it in everyday rehearsals:

Normalize asking for consent: “Can I adjust your arm placement?” should be as natural as saying, “Let’s take that from the top.”

Use boundary check-ins: A quick “How’s everyone feeling about this?” before and after intense work ensures performers aren’t carrying discomfort into the next scene.

Offer opt-in/opt-out language: Instead of “We’re all doing this exercise,” try “Would you like to participate, modify, or observe?”

Give performers agency: Allow them to suggest solutions when something feels off rather than dictating what they should endure.

Lead by example: Directors set the tone. If they model consent culture, the whole room follows.

Choreographing Chemistry: Building Connection on Stage

Choreographing chemistry is about creating an environment where performers feel safe, connected, and empowered to take creative risks. By combining exercises, thoughtful movement direction, and a focus on ensemble alignment, you can help performers forge authentic connections that resonate with audiences.

Reading of Puppy Teeth by Owen Carter, Untellable Movement Theatre, 2024

Movement Dramaturgy: Lynn Panting

On stage, chemistry is magic. It's the spark that transforms a performance from ordinary to unforgettable. Whether it’s the tender connection between lovers, the camaraderie of close friends, or the fiery tension of rivals, authentic chemistry brings relationships to life. For directors and choreographers, fostering these connections is both an art and a science, often rooted in movement and physicality.

Here are practical tips to help performers build trust and connection, ensuring the relationships they portray feel genuine and compelling.

Be Transparent and Set Clear Expectations

Authentic chemistry thrives in an environment where performers know what to expect and feel fully informed about the creative process. Transparency builds trust, reduces anxiety, and allows performers to focus on their work without second-guessing their boundaries or roles.

Outline Goals Early: Share your vision for the scene or performance upfront. Explain the tone, emotional arc, and movement goals so performers understand the bigger picture.

Define Roles and Responsibilities: Clearly outline what is expected from everyone in the room.

Create a Consent-Driven Environment: Establish a clear process for gaining consent and ensure performers know they can revisit or revoke their consent at any time. Encourage open communication about comfort levels and any concerns.

Create a System for Feedback: Ensure that performers have a system to express if they feel comfortable with the direction the scene is taking. This allows for adjustments before discomfort arises.

Be Specific in Direction: Avoid vague instructions like “act more romantic” or “look angrier.” Instead, guide performers with concrete actions, such as “reach for their hand as though you’re unsure if they’ll accept” or “step away, then turn sharply to face them with tension in your shoulders.”

By setting expectations and maintaining transparency, you foster a rehearsal space where performers feel respected, valued, and supported. This foundation not only enhances the chemistry on stage but also ensures a more positive and collaborative creative process for everyone involved.

Trust-Building Exercises

Chemistry begins with trust. Performers must feel safe and comfortable with one another before they can authentically connect. Incorporate trust-building activities into your rehearsal process:

Mirror Exercises: Partners face each other and mirror each other’s movements. This builds focus, awareness, and non-verbal communication.

Contact Improvisation: Encourage performers to explore weight-sharing and gentle physical contact to build trust and understanding of each other’s boundaries.

Eye Contact Drills: Have performers sit across from each other and hold eye contact for extended periods. This may feel awkward at first but can create a profound sense of connection.

Use Movement to Define Relationships

Movement tells a story of its own. The way performers interact physically says as much about their relationship as their dialogue.

Proximity and Space: How close or far apart are the performers? Lovers might gravitate towards each other, while rivals might instinctively maintain distance.

Touch and Tension: A gentle touch on the arm can convey affection, while a hesitant or abrupt movement can suggest discomfort or conflict. Experiment with varying levels of tension in movement to define the relationship.

Rhythm and Energy: Partners who move in sync may appear united, while mismatched rhythms can convey discord or unease.

Align Physicality with Emotional Intent

Chemistry feels real when the physical and emotional align. Help performers connect their movements to their characters’ motivations and feelings.

Embody the Emotion: Encourage performers to explore how their character’s emotions affect their physicality. A confident character might have strong, grounded movements, while a nervous one might fidget or avoid eye contact.

Identify the Stakes: Discuss what each character wants in the scene and how that desire influences their movement.

Layer the Subtext: Teach performers to use subtle gestures and physical cues to communicate what their character isn’t saying out loud.

Prioritize Ensemble Connection

While individual relationships are important, a strong ensemble creates a cohesive, believable world.

Group Warm-Ups: Begin rehearsals with whole-cast warm-ups to foster a sense of unity and shared purpose.

Group Dynamics: Experiment with group movement, such as everyone walking in unison to build ensemble chemistry.

Shared Storytelling: Encourage cast members to view their relationships as part of a larger story, emphasizing the importance of every connection on stage.

Reflect and Adjust

Chemistry is a dynamic process that evolves over time. Encourage performers to reflect on their interactions and adjust as needed.

Feedback Sessions: Create a safe space for performers to share what’s working and what feels awkward.

Revisit Scenes: Chemistry can deepen with repeated exploration. Revisit key scenes to allow performers to refine their movements and relationships.

Celebrate Progress: Acknowledge and celebrate moments of authentic connection.

Choreographing chemistry is about creating an environment where performers feel safe, connected, and empowered to take creative risks. By combining exercises, thoughtful movement direction, and a focus on ensemble alignment, you can help performers forge authentic connections that resonate with audiences.

On stage, chemistry isn’t just about what the audience sees — it’s about what the performers feel. And when performers truly connect, the story they tell becomes electric, unforgettable, and real.

Establishing Boundaries in Creative Spaces

Clear, well-communicated boundaries create an environment where artists feel empowered to take creative risks, knowing their limits and voices are respected.

Artistic environments thrive on creativity, collaboration, and expression, but none of these can truly flourish without a foundation of safety and respect.

Establishing boundaries in creative spaces is not only a professional necessity, it’s a profound act of care. Clear, well-communicated boundaries create an environment where artists feel empowered to take creative risks, knowing their limits and voices are respected.

Why Boundaries Matter in Creative Work

They Foster Safety and Trust

Boundaries ensure that everyone in a creative space feels physically, emotionally, and psychologically safe. Trust is the cornerstone of collaboration, and when participants know their limits will be honored, they are more willing to engage fully in the creative process.

They Encourage Authentic Expression

When individuals feel safe, they can focus on their craft without the fear of being judged, pushed too far, or misunderstood. Boundaries give artists the freedom to explore their potential within a framework that respects their individuality.

They Prevent Burnout

Creative spaces often involve long hours, high emotional stakes, and intense collaboration. Boundaries help manage workload, expectations, and emotional energy, reducing the risk of burnout for everyone involved.

They Strengthen Collaboration

A team that understands and respects each other’s boundaries is better equipped to work together effectively. Open communication about needs and limits allows for smoother interactions and fewer conflicts.

Types of Boundaries in Creative Spaces

Physical Boundaries

Clear guidelines around physical contact are essential, especially in performance arts where touch is often required. Always seek consent before choreographing intimate or physical scenes, and check in regularly to ensure comfort.

Consider personal space in rehearsal or studio environments. Some individuals may need more physical space to feel comfortable and productive.

Emotional Boundaries

Respect the emotional well-being of participants. If a scene or project involves intense themes, create an opt-in culture where individuals can choose their level of involvement.

Encourage performers to share how they’re feeling and be willing to adapt if someone is struggling with the material.

Time Boundaries

Respect participants’ time by setting clear schedules and sticking to them. Avoid excessive overtime or last-minute changes unless absolutely necessary.

Build breaks into rehearsals or creative sessions to allow for rest and recharge.

Professional Boundaries

Define roles and responsibilities upfront to avoid confusion or overstepping. For example, make sure everyone knows who is responsible for feedback, decision-making, or managing conflicts.

Ensure that feedback is constructive and focused on the work, not personal attributes.

How to Establish Boundaries in Creative Spaces

Start with Open Communication

Begin every project with a clear conversation about expectations, goals, and boundaries. Invite everyone to share their needs and make it clear that their input is valued.

Create a Code of Conduct

Develop a written code of conduct or ground rules that outline the standards of behaviour and line of communication for the group. Share this document at the start of the project, and revisit it as needed.

Use Consent-Based Practices

Always prioritize consent, especially in projects involving physical touch, vulnerability, or sensitive themes. Encourage participants to voice their boundaries and remind them they can adjust their consent at any time.

Create a System for Feedback

Establish a system and line of communication to identify and address any issues before they escalate.

Model Boundary-Setting

As a leader or facilitator, set an example by respecting your own boundaries. Whether it’s maintaining a work-life balance or addressing concerns with kindness and clarity, your actions set the tone for the group.

Navigating Boundary Challenges

Even with clear boundaries, challenges may arise. Here’s how to handle them:

Address Issues Early

If someone oversteps a boundary, address it calmly and promptly to prevent misunderstandings or resentment.

Use Neutral Language

Frame boundary discussions as collaborative problem-solving rather than criticism.

Be Flexible

Boundaries may shift as a project evolves. Stay open to revisiting and adapting them based on the group’s needs.

The Benefits of a Boundary-Driven Creative Space